By Victoria Kiefer, Wisconsin Historical Society

May 14-15 is the anniversary of the burning and sinking of the War Eagle in the Black River in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Although the location of the wreck is well-known and it is popular in the community – displayed on everything from banners to road signs – murky water conditions in the river have made it difficult to detail what the ship looks like. Such knowledge could aid preservation efforts for the 148-year-old wreck, which is eligible to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In April, archeologists sought to remedy this by visiting the War Eagle and testing sonar and robotics equipment.

Scientists have been mapping the ocean, lakes and rivers since the 1950s, using sonar equipment to essentially lift off the water and provide a picture of what lies beneath. Sonar is able to do this by emitting pulses of sound waves that bounce off objects, shipwrecks and also the water body’s bottom itself. The length of time and intensity of these pulses returning to the sonar device creates an image. This technology may appear super fancy, expensive and rare, but it is readily available, ranging from low-end devices used by fishermen to high-end systems used by governmental agencies.

No matter the device, the overall goal for sonar scanning is to break the physical barrier that water creates and see what is not easily seen underneath. Maritime Archaeologists Tamara Thomsen and Victoria Kiefer from the Wisconsin Historical Society partnered with Tom Crossmon of Crossmon Consulting LLC to test the use of side scan sonar on the War Eagle shipwreck.

Society maritime archaeologists have collaborated with Crossmon before using side scan sonar, multi-beam sonar and remotely operated vehicles in lakes Michigan and Superior on shipwreck sites that were in water too deep for divers to safely survey. Because of the success of using this equipment on inaccessible sites in the deep, cold and dark water of the Great Lakes, archaeologists wondered if the technology could be used on inaccessible sites in other water conditions. This question led them to the War Eagle site.

The War Eagle was a sidewheel steamship built in Fulton, Ohio, in 1854. It boasted 46 staterooms with fine velvet carpets, luxurious furniture, and even on-board barbershops. Built for the carrying passengers and freight on the Mississippi River, the ship was recognized for transporting troops and supplies from Fort Snelling (Minnesota) during the Civil War, where her only mishap was a stray cannonball that pierced her smokestack while on the Ohio River in 1862.

The War Eagle was a sidewheel steamship built in Fulton, Ohio, in 1854. It boasted 46 staterooms with fine velvet carpets, luxurious furniture, and even on-board barbershops. Built for the carrying passengers and freight on the Mississippi River, the ship was recognized for transporting troops and supplies from Fort Snelling (Minnesota) during the Civil War, where her only mishap was a stray cannonball that pierced her smokestack while on the Ohio River in 1862.

After the war, the War Eagle again carried passengers and freight between the bustling towns along the Mississippi River. Connections between ships and trains made ports like La Crosse important transportation hubs for settlers moving to the western frontier.

On the night of May 14, 1870, the War Eagle dropped off passengers at the La Crosse City Landing on the Mississippi River at State and Front streets, then proceeded up the Black River to the Milwaukee Road Depot to load cargo and meet the midnight train from Milwaukee. While barrels of highly flammable Danforth Non-Explosive Petroleum Fluid were loaded, one was discovered to be leaking. As the ship’s carpenter was tightening the bands, the barrel caught fire, and soon the ship’s deck was ablaze. They tried to roll the barrel into the water over the port side, but the barge Webb was docked alongside. Reports claim that the flames engulfed the barge, the dock, the depot, many of the train cars, and several warehouses and grain elevators. In addition to the War Eagle, the barge was lost, and two steamers were damaged. Many of the passengers lost all of their worldly belongings in the fire and seven passengers lost their lives.

The War Eagle now lies in 16 feet of water near the shore of the Black River. Due to its popularity, early divers as well as non-divers heavily looted the site. To provide some protection it was considered for nomination on the National Register in 1980, but was only determined eligible pending further study. The river’s current along with water clarity that can only be described as “diving through mud” makes archaeological survey conditions poor and often hazardous. All of these variables made the War Eagle shipwreck the perfect place for the equipment test. If successful, archaeologists would have better knowledge of this well-known site and new methods of surveying many submerged cultural resources that reside in lakes and rivers with the same water conditions as the War Eagle site.

The test first began with locating and obtaining a general overview of the shipwreck site using a high-tech fishfinder, a down-looking sonar device attached to the hull of the Crossmon Consulting’s boat. This took multiple circular passes over the site to determine the best method of moving forward.

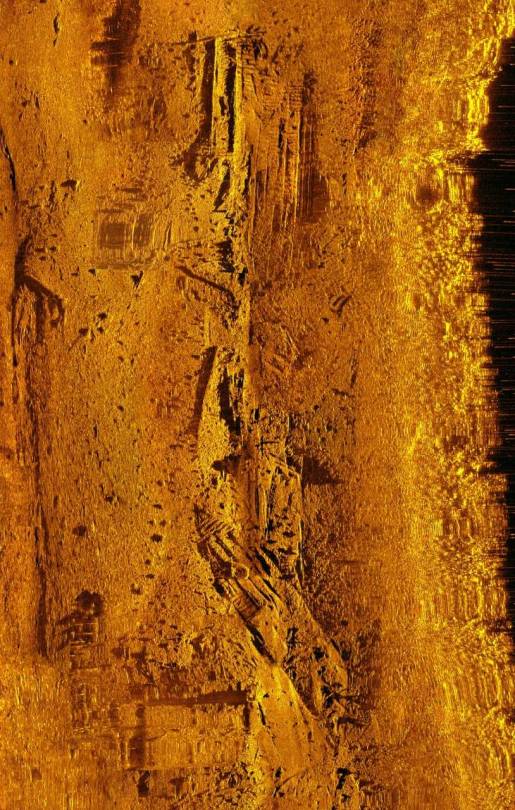

The next step was lowering the Sea Scan ARC Explorer towfish from Marine Sonic into the water. This device is towed behind the vessel, allowing researchers to move the towfish up and down in the water column to get a more precise view of what is on the bottom. Although extremely useful for obtaining detailed images of deep shipwrecks, for shallow wrecks like the War Eagle, collecting detailed imagery while fighting a current and avoiding hitting the bottom or any part of the shipwreck proved tricky.

To the confusion of any onlookers, the team spent more than six hours driving in circles over the wreck, testing equipment and gathering as much data as possible. Archaeologists initially considered putting an ROV on the site, but soon decided it was not worth the risk of loss or entanglement while also fighting the current and lack of visibility.

Testing the sonar equipment was a success, providing a never-before-seen image of the War Eagle shipwreck site in its entirety. The Marine Sonic technology also allowed for measurements to be taken from the side scan sonar images. These tools will help archaeologists better understand the events that occurred during the fire that resulted in the loss of the War Eagle, as well as the Milwaukee Road Depot complex, and provide more information on the construction and use of river steamboats in the region.

Spending the day driving in circles also allowed archaeologists to study the technology and its use in these specific water conditions. The success of this field test may be a springboard for research of submerged resources under Wisconsin’s other inland waterways.