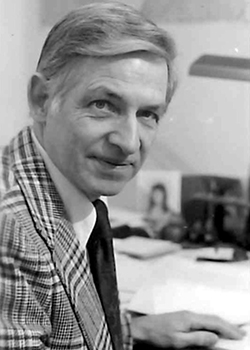

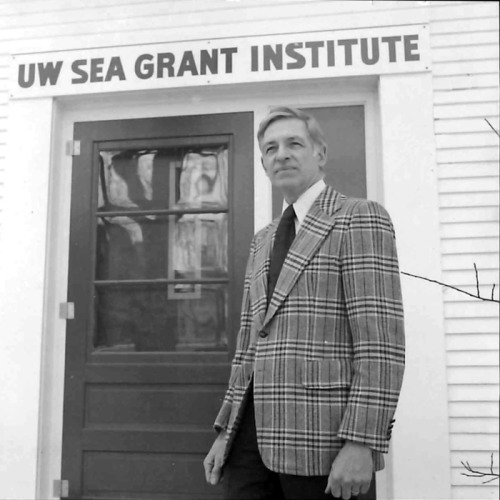

The first Wisconsin Sea Grant Director, Robert Ragotzkie

Fifty years ago in 1968, the Wisconsin Sea Grant Program was funded for formation at the University of Wisconsin. We didn’t actually start providing grant money for research projects for a few years. Because that’s one of our main purposes, we’ve chosen to wait a few more years before we start any 50th anniversary hoopla.

Another reason we’re waiting … (and this might be way more information than you want, but I’m going to do it anyway) is that we weren’t designated as an official Sea Grant College Program until 1972. When Sea Grant programs are formed, they go through a series of four phases: a Sea Grant Project, a Sea Grant Coherent Area Program, a Sea Grant Institute, and then a Sea Grant College Program.

Official program status is only awarded by the federal government if certain criteria are met, including demonstrating excellence in fields related to ocean, coastal and Great Lakes resources. Safe to say, it’s a big deal to finally reach college status.

In the meantime, we’re working behind the scenes to gather information in preparation for the occasion of the 50th anniversary of our official designation as a Sea Grant College Program. (These things don’t just happen overnight!) As part of this effort, I had the chance to speak with Wisconsin Sea Grant’s first director, Robert Ragotzkie, 94, about his memories of the program’s formation and why he was interested in being part of it.

Our conversation was enlightening. Here are some highlights:

Bob, as he likes to be known, was also involved in ensuring that the Great Lakes were included when Sea Grant itself was coming into being. Here’s what he said, “I went to an early Sea Grant conference in 1967 or ’68. Athelstan Spilhaus conceived of Sea Grant and the focus was on university programs located on the oceans. I went to this conference at Rhode Island along with a Michigan representative. We pointed out to him (Spilhaus) at this conference that the Great Lakes were like the oceans and should be part of the program. There was a lot of give and take but ultimately, we agreed that the Great Lakes should be part of the Sea Grant program. We were included then in the first awards for Sea Grant programs to universities. That was the beginning. From then on, we were part of the program.”

By the early 1980s, the program was active throughout the full university system. “That was a unique part of it as far as we were concerned,” Bob said. “It wasn’t just University of Wisconsin-Madison or University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. It was seven different campuses in the UW System plus two private universities were included. That’s what made it different from all of the other proposals/projects.”

Another thing I didn’t realize was that the early scope of the program was broader than it is now.

“The program initially concentrated efforts and research on all five Great Lakes. We had a Great Lakes Program (at the university already) but it was not very well organized. This sort of pulled it all together. Michigan Sea Grant was also Great Lakes-wide and we had close cooperation with the University of Michigan Sea Grant Program,” he said.

Bob also put in a plug for the UW-Madison Go Big Read book, “The Death and Life of the Great Lakes” by Dan Egan.

“If you look in the back of that book in the bibliography, I’m pretty sure that an awful lot of those research papers came from Sea Grant. If you read that book, you realize how different the Great Lakes are from the oceans. In the past 100 years, the Great Lakes have changed enormously. The oceans are also changing but not as much or as fast because the oceans are bigger. That book is a classic in how the Great Lakes work. I think it represents how we look at science now (in a more holistic manner) than how we looked at it 50 years ago and how research was done then. Dan Egan did a beautiful job writing that book … It epitomizes how Sea Grant works. It doesn’t concentrate on one particular species or harbor but on the Great Lakes as a whole and how they function.”

Bob is still keeping track of who is conducting research in the Great Lakes. He knows the people even though he has been retired for 38 years. However, the main way he monitors the health of the ecosystem is via a much more concrete way.

Bob is still keeping track of who is conducting research in the Great Lakes. He knows the people even though he has been retired for 38 years. However, the main way he monitors the health of the ecosystem is via a much more concrete way.

“I’m a sports fisherman and that’s how I keep track of things. Anything I can catch on flies I like – from speckled trout all the way up to tuna and swordfish. You name it, I’ll fish for it.”

A worthy endeavor if ever I’ve heard one.

(Post originally published Nov. 15, 2018)