Some of the most iconic invasive species–zebra and quagga mussels–are in this division. They compete across the country in the invasion game and have been in the game for more than 30 years. We think it will be tough to upset them, but the other species in this division have some strong points that could lead them to an upset. Whether it’s engaging unique stakeholder groups or showing large economic impacts on a single lake, we expect to see some tough battles for our least-wanted macroinvertebrate.

Zebra and quagga mussels

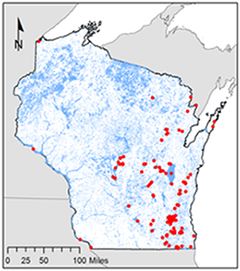

Zebra mussel dist. Credit: Jake Vander Zanden, UW-Madison

Up next, a team everyone likes to root against: the Dreissenids. This year, the zebra mussel teamed up with the quagga mussel for the tournament, which may give them a slight advantage over the other macroinvertebrates in the field. The two species are closely related and, between the two of them, both have tallied up wins all over Wisconsin after arriving via ballast water in cargo ships not too long ago. Zebra mussels are found in nearly 250 lakes in Wisconsin, while the quagga mussel has yet to bring its invasion game inland and is limited to the Great Lakes.

Both species can grow to about two inches long and have patterned shells, but you can tell the difference on the court by looking at their shape. Quagga mussels hold an elliptical shape, while zebra mussels have a flat bottom that allows them to stand up like a prism. The invasive mussels compete with native mussels and macroinvertebrates by filtering the available phytoplankton; a scrimmage game between these two groups would be painful to watch.

When mussel species are young, they’re microscopic, making them difficult to detect by humans. Perhaps they might even sneak into intake pipes of watercraft. When they’re older, however, they grow larger and stick to hard surfaces using byssal threads that act as tiny feet, allowing them to clog those intake pipes they’d been calling home.

These species have a reputation for traveling. If you’re worried about zebra or quagga mussels coming to a waterbody near you, you can prevent the spread by draining water from equipment before transporting it. Additionally, make sure to clean and dry anything that’s touched the water.

Spiny waterflea

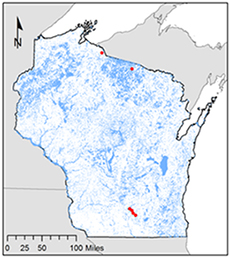

Credit: Jake Vander Zanden, UW-Madison

At less than a ½ in tall and under 10 wins across the map, you’re probably wondering how the Spiny waterflea snuck its way into this tournament. Perhaps you’re wondering what a Spiny waterflea even is? This tiny crustacean blends in with native zooplankton, but when fish try to eat it, the waterflea’s sharp spine wreaks havoc on the fish’s insides. Further, it competes with native zooplankton and disrupts the bottom of the food chain.

These species can set the groundwork for world records without even some of the world’s best limnologists noticing – just see Lake Mendota. The world’s highest densities of spiny water flea were recorded in Lake Mendota and they were likely present for years before being detected on one of the most studied lakes in the world. They have also been implicated in declines in water quality that could cost millions of dollars to reverse. Even though they’re relatively new to Wisconsin’s inland lakes, their already demonstrated impact gets them a spot in the tournament.

The microscopic resting eggs of spiny water fleas can survive outside of water for up to half of a day, making their ability to spread pretty alarming. If you want to get a closer look they’ve been found clumped up like snot or gelatin on fishing lines. That being said, to prevent their spread into your favorite waterbody, make sure to inspect, clean, and dry all fishing gear upon exit and entry of a waterbody.

New Zealand mudsnail

Another new team trying to prove itself this year is the New Zealand mudsnail. While they may be small (less than 1/5 in long), and they have very few documented wins in Wisconsin, they’ve got some strengths that could see them go deep in the tournament. First, they can close their operculum and live outside of water for up to thirty days. Second, their small size permits them to easily hitch a ride on waders from the trout streams where they reside. Third, female New Zealand mudsnails are born pregnant, which makes it so only one could start a whole new team.

Another new team trying to prove itself this year is the New Zealand mudsnail. While they may be small (less than 1/5 in long), and they have very few documented wins in Wisconsin, they’ve got some strengths that could see them go deep in the tournament. First, they can close their operculum and live outside of water for up to thirty days. Second, their small size permits them to easily hitch a ride on waders from the trout streams where they reside. Third, female New Zealand mudsnails are born pregnant, which makes it so only one could start a whole new team.

You might be able to spot them by counting 7-8 whorls and looking for a brownish colored shell. Since they’re relatively new to Wisconsin, reporting new invasions can help prevent their spread. If anglers and other water users take care to scrub waders and footwear, and clean and drain all equipment that’s been in contact with water, New Zealand mudsnails may fizzle out and not even make next year’s tournament.

Rusty crayfish

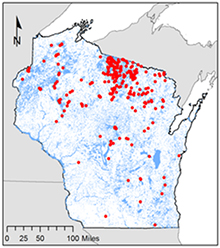

Credit: Jake Vander Zanden, UW-Madison

The rusty crayfish has been a constant presence in the invasion game. And while they might not have the flash of the zebra and quagga mussels, their style of play can result in large impacts on Wisconsin’s lakes. This very aggressive species will eat just about anything, from plants to small fish.

Rusty crayfish eat by chopping up plants, which could wind up spreading other invasive species that develop new plants when fragmented, like Eurasian watermilfoil. Their direct impacts, plus how they can facilitate other invasions, make them very unwanted.

You can identify the rusty crayfish by looking for dark, rust-colored spots on their carapaces and spotting black bands on the tips of their claws. They displace native species by taking their homes and eating their food sources.

You can prevent the spread of the rusty crayfish by taking precautions to not use live crayfish as bait and only using bait from licensed bait dealers. After all, the reason this species came to dominate this tournament was via the bait trade. Also, remember to never release plants, fish, or animals into any body of water.