The scow schooner Silver Lake, built in 1889, met its end only 11 years later in dense, early-morning fog on Lake Michigan. Around 3 a.m., the car ferry Pere Marquette, a much larger vessel, struck the Silver Lake and nearly broke it in half. All but one crew member escaped to safety as the ship sank. Now, the wreck of this scow, which once transported lumber on Lake Michigan, lies about seven miles northeast of Sheboygan.

It’s a dramatic tale that is compelling not only for the human drama, but also because it sheds light on the types of vessels that have powered Great Lakes shipping, recreation and more.

WHS/Sea Grant maritime archaeology summer fellow Tori Galloway. (Submitted photo)

These stories fascinate Tori Galloway, a summer fellow jointly sponsored by the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHS) and Wisconsin Sea Grant. Her main task is conducting a comparative analysis of scow schooner construction and use on the Great Lakes, as well as their evolution and use in other locations.

Scow schooners filled a particular niche in the world of Great Lakes shipping from roughly the 1820s to the turn of the century, when they were replaced by steam-powered vessels. Said Galloway, “They’re smaller vessels than the typical schooners. They are square, stubby vessels that maximized their cargo spaces, and [their design] also allowed them to get into shallow ports and rivers, so they really expanded trade routes in a way that hadn’t been done before.”

A recent graduate of Indiana University, Galloway is based for the summer in the WHS’ Maritime Preservation and Archaeology Program, where she works closely with archaeologists Tamara Thomsen, Caitlin Zant and Tori Kiefer. Galloway will return to Bloomington at the end of the summer to continue in the graduate program in archaeology.

Eight known scow schooners lie in Wisconsin waters. Galloway is trying to visit all eight and study them by diving, wading or using an ROV (remotely operated vehicle).

Said Thomsen, “These scows were very utilitarian little vessels. We see often that they were constructed on the shores of the lakes or rivers by newly arriving immigrants, perhaps with little experience in shipbuilding or shipwright skills. Although unglamorous and mostly uncelebrated vessels, scows were an entry point into the maritime trades for many. In some cases, we see through historical analysis that these vessels were passed on to newly arriving family members as ship owners gained success and worked their way up into larger vessels.”

Scow schooners were also used in places like San Francisco and New Zealand. Learning more about specific construction types will be part of Galloway’s work. “The first New Zealand scows were named after the Great Lakes and their construction is obviously descended from North American vessels,” but then adapted to local needs, said Galloway.

Though she has always loved spending time on the water boating and kayaking, the Fairmount, Indiana, native got into diving and maritime archaeology almost by accident. Indiana University has an academic diving program, and she signed up for a scuba diving class for fun. That led to research meetings and field projects as her passion for maritime archaeology grew.

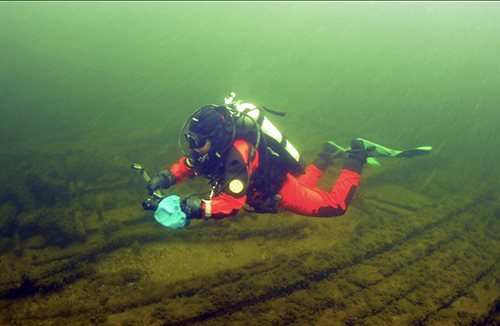

Tori Galloway on a dive to study the scow schooner Dan Hayes, which sank in 1902 near the city of Sturgeon Bay. (Photo: Tamara Thomsen)

Said Thomsen, Galloway’s mentor at WHS, “Tori comes to us as an experienced and comfortable cold water diver. Through her summer fellowship, she is learning more advanced diving skills and techniques.”

Galloway also brings skill in a type of 3D modeling known as photogrammetry. Explained Thomsen, “For each of the wrecks that she visits, she has been creating models of the wreck sites in order to more effectively share their stories and build stewardship by virtually connecting divers and non-divers to the resources.” (To see an example of Galloway’s 3D modeling, view this model of the I.A. Johnson, which sank in 1890 and now lies in 90 feet of water near Sheboygan.)

In addition to research, Galloway will take part in outreach events this summer with WHS and Sea Grant, including the Tall Ships Festival in Green Bay in July and various Wisconsin Water Library events.

Galloway’s WHS/Sea Grant fellowship builds on her prior experiences, including a summer 2018 internship in the Maritime Heritage Program at the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Last month, she completed her bachelor’s in anthropology and underwater archaeology, with a certificate in underwater resource management.

When she returns to IU after her time in Wisconsin, she will work full-time as a visiting lecturer at the university’s Center for Underwater Science while also pursuing graduate studies.

To learn more about Wisconsin shipwrecks, visit wisconsinshipwrecks.org, a joint project of WHS and Wisconsin Sea Grant.