Lake sturgeon have been on the planet for 150 million years. Despite that long residency, scientists are still learning about these fish, the largest found in North America. An enduring question is what contributes to their survival skills. Answer: Sound. As one factor anyway.

Based on biological examinations and detailed field recordings of the infrasonic sounds of this ancient fish, an article in the December 2014 Journal of Applied Ichthyology, bit.ly/1wdGt1j explains size may be one of the reasons why Wisconsin researchers believe sturgeon, which can reach a weight of more than 200 pounds and exceed 8 feet, achieve sounds so low that most of their energy escapes normal human hearing. The sounds apparently aid reproductive success.

“Along with known physical cues from river temperature and substrate, the fish likely combine visual, acoustic and electrical sense information into an adaptable suite of wide-ranging sensory knowledge, a powerful suite of perceptions that has undoubtedly assisted lake sturgeon in successfully propagating their species for 150 million years,” said Chris Bocast, a Ph.D. acoustic ecologist who obtained the field samples while working for Wisconsin Sea Grant as an audio specialist. He is the lead author on the paper, along with Ronald Bruch and Ryan Koenigs, both biologists with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

At one time, Bruch thought the sound was the result of the force of the large fish hitting each other or the water. The journal article reports that the actual biological mechanism employed by lake sturgeon in producing drumming sounds has not yet been confirmed. Thanks to the interdisciplinary scope of the exploration, however, researchers can put sturgeon in the company of whales, elephants and other large creatures whose sonic capabilities reach into the infrasonic.

In addition to the drumming “thunder,” Bocast collected sturgeon sounds best described as crisp crackles; sharp knocks or raps, similar in tonal character to humans snapping their fingers or rapping a tabletop; and squeaky whistles, sonically resembling a dolphin or human whistle.

In each instance, the sounds seem to play a role in reproduction as they either precede spawning or are timed with gamete release. Communication through sound may be key to enabling reproductive success—matching gamete release to the presence of females as well as attracting multiple individual males to spawn, increasing genetic diversity. The journal notes that previous research has observed sturgeon in the field responding to drumming from distances up to nearly 17 feet.

The findings also validate generations of indigenous knowledge. Those living near waters populated by sturgeon have long reported faint drumming sounds and vibrations. Native-Americans in Wisconsin’s Fox and Wolf River watersheds characterize the arrival of this mysterious “thunder” as the onset of spring sturgeon spawning runs.

Lake sturgeon were nearly extirpated from Great Lakes waters, where they were once prevalent. Wisconsin’s population is one of the healthiest in the world. In fact, most wild populations around the globe only persist due to human stocking from aquaculture facilities. Consequently, any data that sheds light on sturgeon reproduction take on critical importance for fisheries managers seeking to re-establish breeding sturgeon in former habitats or enhance existing stocks, Bocast said.

In the Great Lakes, historically, lake sturgeon decline had been due to overfishing, as well as pollution from the lumber industry and agricultural runoff. Prior to their overfishing in a quest for caviar and meat, people regarded lake sturgeon as a nuisance fish and killed them without making any other use of them. In contemporary times, the fish are protected but still face challenges posed by pollution, climate change and dams.

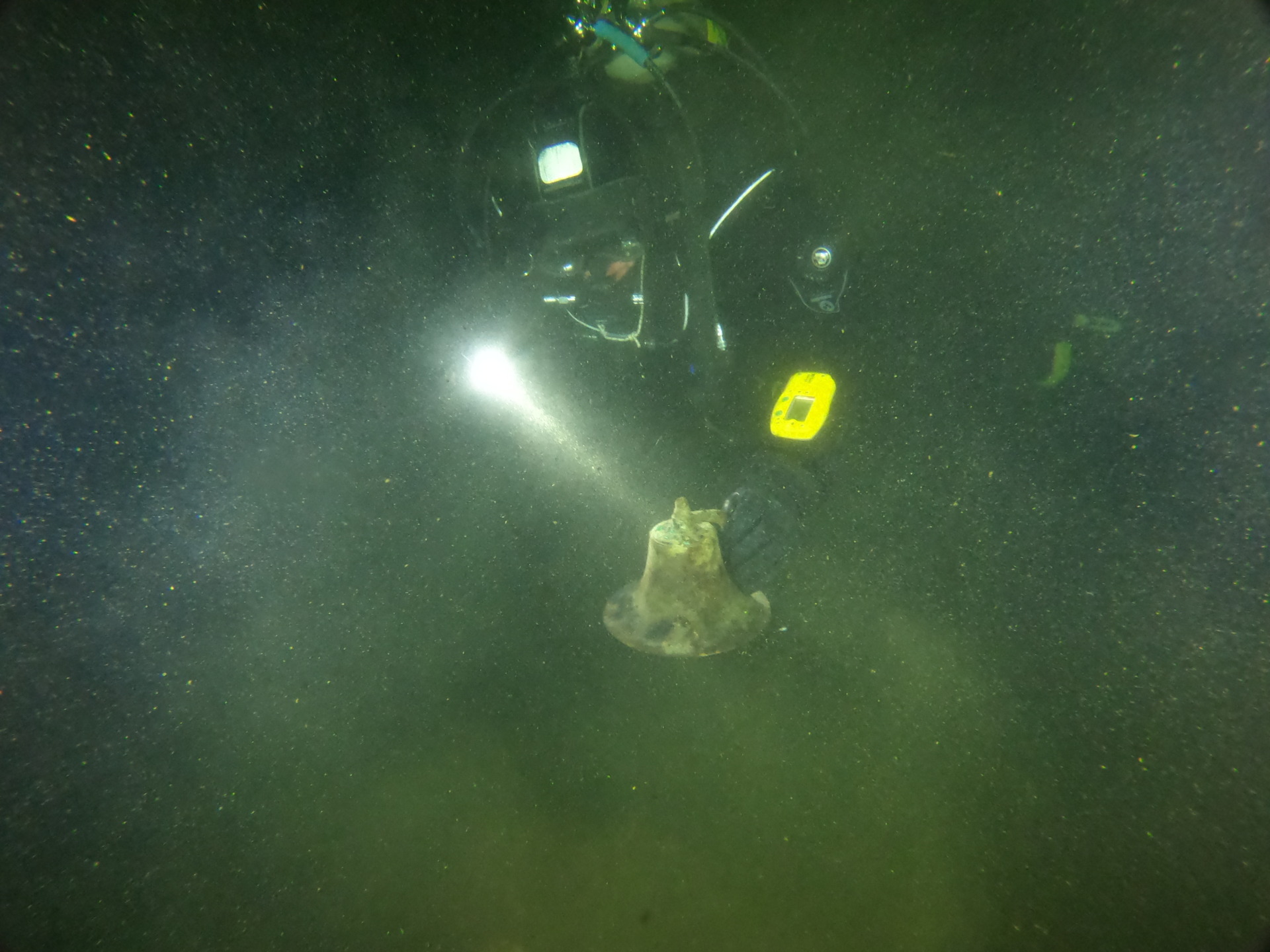

The recordings detailed in the journal article are the first captured in the field. Previous published research on sound production has all been documented in tanks, using methods to artificially stimulate the fish to produce sounds. Bocast noted that this investigation, conducted in the field and one which monitored the natural behaviors of the fish, should provide important contextual information—more meaningful data from a fisheries management viewpoint.

“One of the reasons I’m excited for the work to get out there is to see how other folks working the in the field can interpret and utilize the results,” Bocast said.

The study was supported in part by Sea Grant, DNR and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies.

Listen to sturgeon “thunder” at bit.ly/ZYMOiE