Not long ago, the muck dredged from the bottom of the Duluth-Superior Harbor had a bad name. People referred to the navigational channel material as dredged “spoils,” giving the impression that it was somehow spoiled and unfit for use. That might have been true when the harbor was more polluted, but now, the relatively clean sediment is in demand as soil for restoration and building projects.

Dredging has a long local history. Gene Clark, Wisconsin Sea Grant’s coastal engineer, explained that dredging of the harbor began in the late 1800s and early 1900s, after storms demolished breakwaters built offshore of Duluth. The more-protected harbor was naturally shallow and needed to be deepened to allow ship traffic.

This early dredging material was deposited in the harbor to form Hog and Barker’s islands in Superior, Interstate Island on the border between Wisconsin and Minnesota, and Herding Island in Duluth. In the late 1970s, Erie Pier was constructed for dredged material disposal on the Minnesota side of the river near the current Bong Bridge. Today, between 100,000 and 125,000 cubic yards of material is dredged annually from the harbor.

Designed to hold 10 years’-worth of material (1.1 million cubic yards), the facility, managed by the Duluth Seaway Port Authority, is still in operation today due to modifications that allow it to hold double the amount of material (2.2 million cubic yards). Erie Pier is nearly filled to capacity now, and has switched from operating as a confined disposal facility to a processing and reuse facility.

Erie Pier contains two grades of material: “coarse” and “fine.” The sandy coarse material is in demand for projects like beach replenishment on Park Point and for construction. The second material – fine silt and clay – has been used for several demonstration projects such as mineland reclamation on Minnesota’s Iron Range, providing fill for the Northland Country Club in Duluth and for turf restoration at the city of Superior landfill.

These “fines” are more problematic for use and were in less demand until they were found good for growing plants and restoring habitat, Clark said. Thanks to federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative funding and the efforts of many local groups, several aquatic habitat projects that could use this fine material are planned.

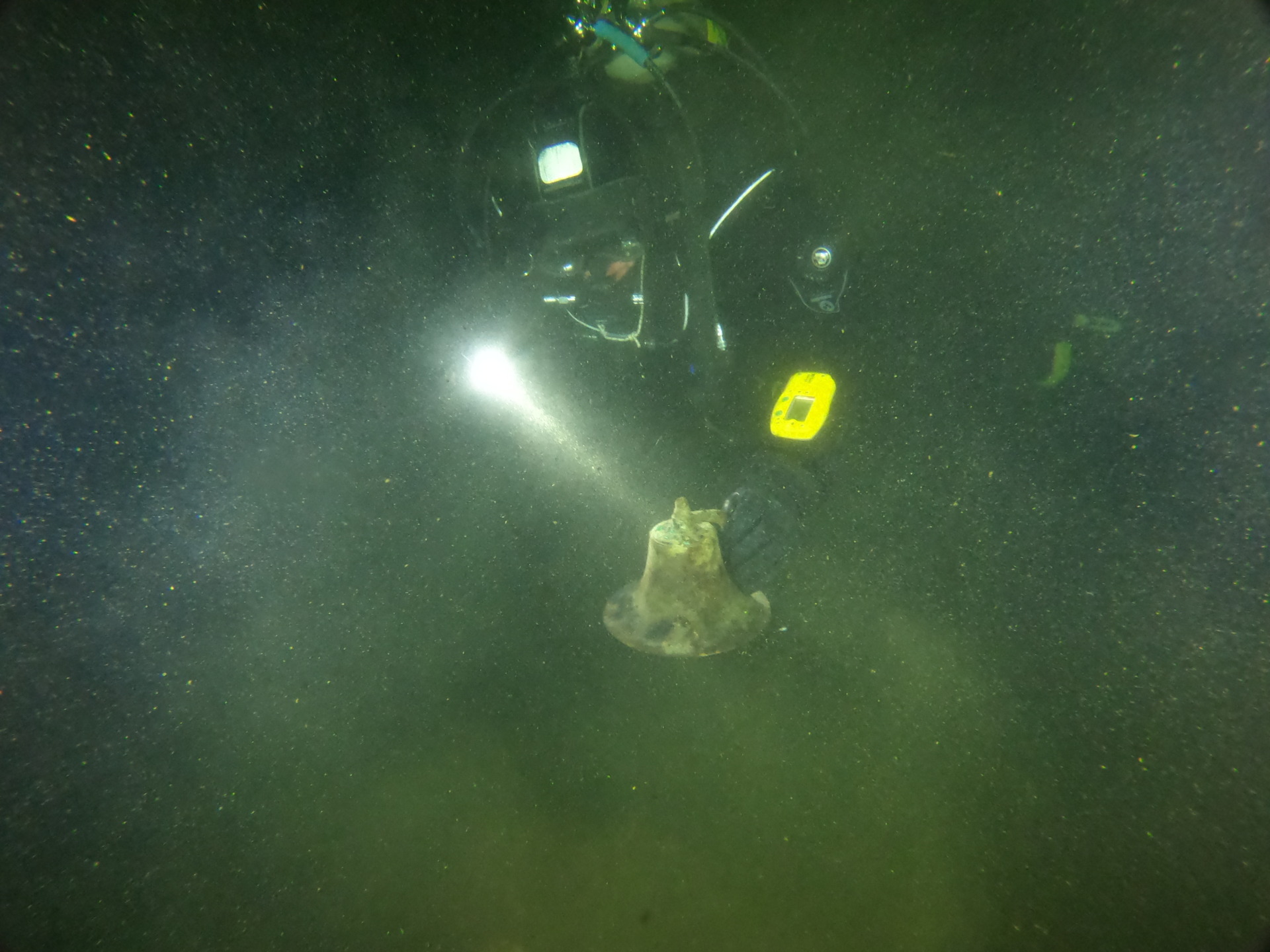

The most recent restoration project can be seen if a person drives on Highway 53 on the Minnesota side of the Blatnik Bridge. The 21st Avenue West project, as it’s known, is a pilot project that has saved three years of material from being deposited in Erie Pier. Instead, it’s been deposited in the 21st Avenue West bay to form several underwater islands

and to fill parts of a shipping channel no longer in use. The Army Corps of Engineers and other project partners are monitoring for any movement of the material to ensure it won’t interfere with shipping before additional material is deposited to restore more aquatic habitat in this and other harbor areas.

Another project is the 40th Avenue West bay, which when combined with the future project at 21st Avenue West would use more material than is currently in Erie Pier, said Clark. He is a member of a local Dredging Subcommittee (of the Harbor Technical Advisory Committee), which looks at short- and long-term strategies for handling and reusing the dredged material. Other members of the team include staff from the Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Council, Minnesota Sea Grant, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Duluth and Superior port authorities, the Wisconsin and Minnesota departments of natural resources, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, engineering firms and the University of Minnesota Duluth. Their efforts resulted in a management plan for Erie Pier, which was completed in 2007 and is being updated.

“Everyone’s giving a sigh of relief,” Clark said about the current demand for dredged material. “But the worry about Erie Pier filling up is still there. If something were to happen and we couldn’t continue to use the material for the restoration projects, we’d only have three to five years left before Erie Pier fills up again and we might have to spend millions of dollars to create a new facility.”

Clark’s worries extend to an even longer view, also. “What happens after the proposed restoration projects are completed? The harbor will still be dredged every year and we’re going to be asking the same question 10 years from now. We need to find other sustainable uses for the material and a way to make using it fiscally feasible.”

Clark mentioned the possibility of using dredged material on land for brownfield redevelopment and restoration of the U.S. Steel Superfund Site in Morgan Park. The subcommittee is also looking at ways to place dredged material in deep spots in the harbor that perhaps don’t need to be so deep – referred to as “open water placement.”

“We’ve bought some time for Erie Pier,” Clark said. “If using the material for the restoration projects works out, we’ve bought a lot of time.”