Lydia Salus grew up about 20 miles from Lake Michigan, in a Wisconsin village graced with Mammoth Spring, where water seeps through cracks on top of the shallow aquifer that underlies much of Waukesha County.

Since her formative years, water has been a part of Salus’s life. As an undergraduate, Salus worked on a project to facilitate fish passage through urban culverts. She got a master’s degree in water resources management with a focus on hydrology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison with the intention of becoming a hydrologist devoted to ecological restoration.

Although that career in restoration shifted in 2018 when she signed on as an assistant to the Southeastern Wisconsin Coastal Resilience Project, Salus remains tied to water. Right now, her connection is through a brand-new initiative to increase coastal resilience on Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan shoreline.

The new project builds on the previous one, which assisted people in Kenosha, Racine, Milwaukee and Ozaukee counties in responding to rising lake levels—offering information on how to stabilize bluffs, address erosion and protect infrastructure.

A southeastern Wisconsin house teeters on the edge of a bluff after coastal storms and waves eroded the shoreline 40 feet in four years. This house was later demolished

It was also notable for encouraging conversation and cooperation among the whole mix of lakefront property owners—between private property holders and municipalities, counties, state agencies and federal partners.

Termed Collaborative Action for Lake Michigan (CALM) Coastal Resilience, the project places Salus at Sea Grant. The Wisconsin Coastal Management Program and State Cartographer’s Office are the other members of this three-way partnership that, according to Salus, increases capacity to reach and serve communities.

“The Southeastern Wisconsin Resiliency project was a really good start for taking a regional approach to addressing hazards. Hazards don’t just go away,” she said. “That earlier project was good at building momentum in those communities, so then we just wanted to expand that up the coast to other communities and share that momentum with them.”

CALM is funded by what Salus termed “an exciting grant; a competitive grant for something called a project of special merit” from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and which was awarded to the Wisconsin Coastal Management Program. It will strive for three outcomes:

- Increasing collaboration across all stakeholders.

- Developing, revising or adopting local ordinances, plans or policies that are going to help build resilience in coastal communities.

- Fostering regional prioritization of hazards that need to be addressed so that when opportunities for collaborative action are available, community leaders are ready to capitalize.

CALM is a nearly $250,000 18-month undertaking that kicked off in October 2021 and will conclude in March 2023, making it, as Salus said, “A quick turnaround, but we already have a good framework to build off of. I think it’s a little bit easier to implement because we have something that we know worked (with the Southeastern Wisconsin Coastal Resiliency Project).”

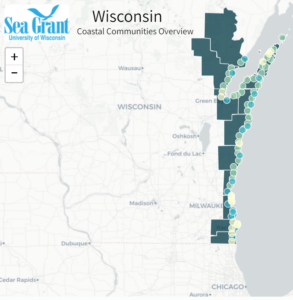

When fully in the swing of the initiative, Salus will organize field trips, pandemic willing, to highlight coastal challenges and solutions. Additionally, she will host meetings to share case studies and tools, and support communities talking with each other and determining regional priorities. Those communities include 11 counties, 18 cities, 16 villages and 36 towns stretching from the state’s border with Illinois up the Lake Michigan coastline to the state of Michigan.

Wisconsin’s Lake Michigan communities will participate in a new program to build resilience in the face of flooding, erosion and infrastructure damage.

The types of folks involved are those housed in state and federal agencies, local and state elected officials, coastal engineers and landscape professionals, municipal technical staff members, people from academic institutions, sewerage districts and regional planning commissions.

Salus said she is feeling energized by the chance to bring together so many people through a process that embraces “stakeholder-driven prioritization. I really like that term because we have built into the project the process of getting feedback from the communities. We are starting off with a survey of their needs, so we are then presenting tools and resources and bringing in speakers that are going to be helpful to them.”

Salus is also feeling personally energized as this new initiative gets underway, saying she appreciates the “unique challenge that balances the human-environment interaction. There are naturally occurring processes on the lake that wouldn’t necessarily cause issues if we didn’t have a built environment along the lake, if we didn’t have people living there.” She said she looks forward to the applied science that can address these coastal hazards that are certainly not going to disappear.