As a diver, Tamara Thomsen can see not only down through the waves but also into the past. As it turns out, following a recreational frolic last summer using a type of underwater scooter, she can see quite far into the past.

Tamara Thomsen beams while standing over a water-filled crib that holds the 1,200-year-old dugout canoe she discovered. The canoe is undergoing a preservation process in the water that will ready it for eventual public display. Photo: Moira Harrington

That day in June 2021 Thomsen, a maritime archeologist with the Wisconsin Historical Society (WHS) and longtime Wisconsin Sea Grant collaborator, discovered a 1,200-year-old dugout canoe, the oldest intact shipwreck found in Wisconsin. It also had artifacts with it.

Thomsen knows shipwrecks. She has prepped dozens of nominations for lakes Michigan and Superior shipwrecks for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. She is the driving force behind the popular WHS/Sea Grant joint website wisconsinshipwrecks.org. She has been inducted into the Women Divers Hall of Fame. Along with fellow marine archeologist Caitlin Zant, she recently worked with educators to create six distinct maritime educational activities based on data from previous Sea Grant projects on Wisconsin maritime archaeology. With Sea Grant project support, in 2021 Zant and Thomsen delivered 11 maritime historic preservation presentations that reached nearly 530 people.

Floating onto this already impressive scene is the dugout canoe. The tale of its first sighting is a lesson in serendipity and the value of strong-arming a colleague to double-check on a chance encounter that Thomsen describes with a chuckle as, “Swimming around under the water, I don’t see logs, I see dugout canoes.”

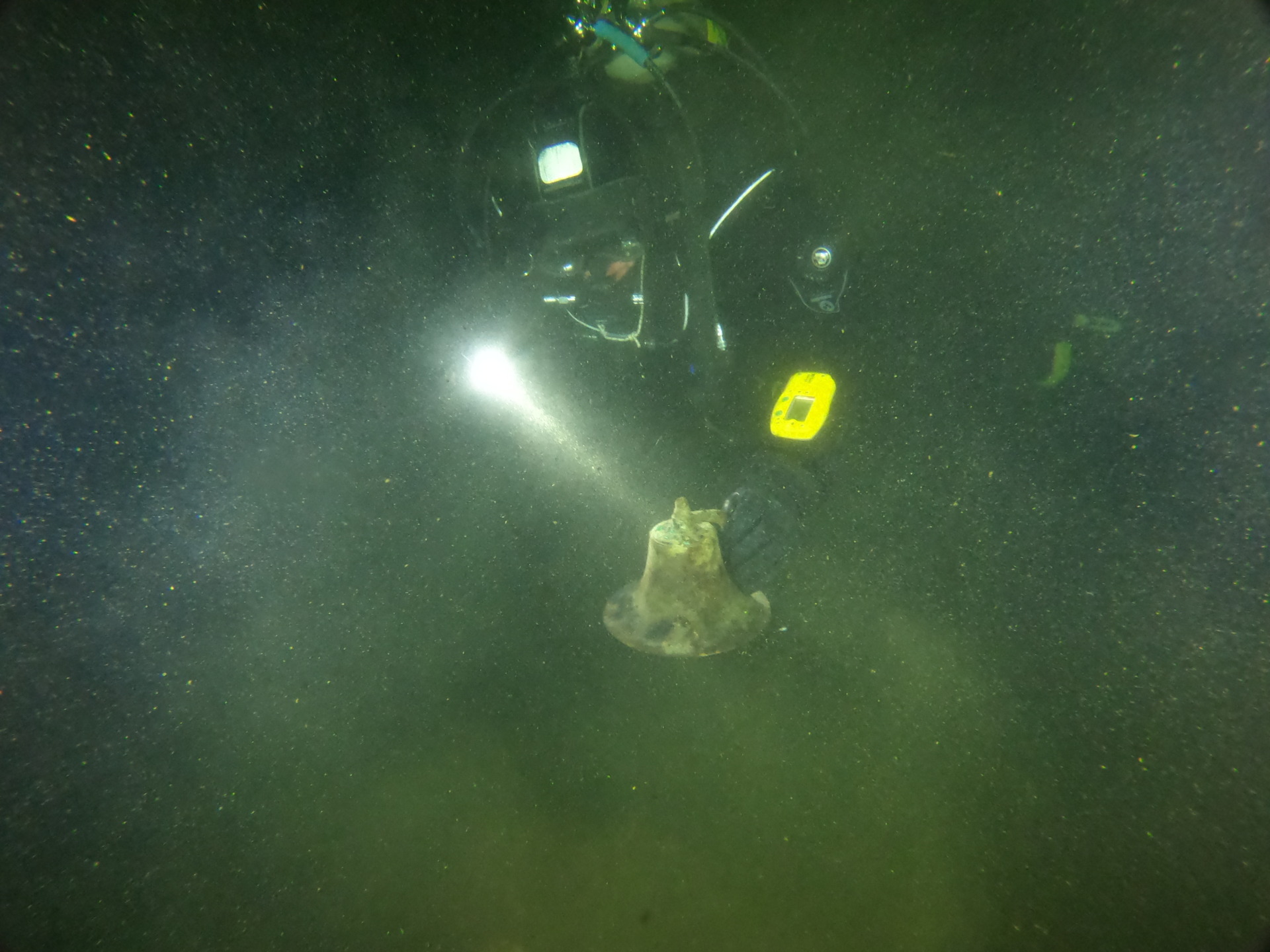

That discovery day, after she spotted what she thought was a partially submerged-in-sediment canoe in 26 feet of water, Thomsen needed to return to land because her underwater scooter partner at the time had reached the designated turn-around point for the air volume in her tank. Thomsen, however, was itching to go back and pursue her hunch that this was more than any old chunk of wood. On that same Saturday, Thomsen convinced a colleague, Amy Rosebrough, to accompany her in a boat back to the site following the coordinates she had noted on the first go-round.

Rosebrough is not a diver. She is a WHS terrestrial archeologist, but Thomsen knew she would make a good sounding board for assessing the site. At the marked location, Thomsen descended in her diving gear once more, gently shifting sediment to get a better look at the sunken craft. She also resurfaced with seven flat stones, some notched, which had been resting in the canoe. After Rosebrough’s examination, Thomsen replaced the stones in the canoe, and replaced sediment around the canoe to offer it protection.

The pair returned to shore and Rosebrough spent the evening pondering the assortment of rocks, which she then deduced were sinker weights for a fishing net, a net long since lost in the waters of Lake Mendota, one of Madison, Wisconsin’s, four lakes.

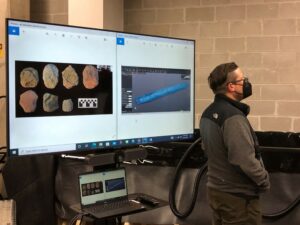

The seven rocks recovered with the canoe are pictured to the left on a large electronic display in the room where the canoe is being preserved. On the right side of the screen is a 3-D image of the canoe. Photo: Moira Harrington

The canoe’s discovery fell at a time of transition for the WHS. James Skibo, the state archeologist, had just come onboard. While giving him a few weeks to settle into his new role, Thomsen and Zant also kept reminding him about the canoe, soon fully enlisting his help in further investigation. Skibo and Thomsen went back to the lake and retrieved what Skibo termed a piece of wood “about the size of a piece of hair” for radiocarbon dating.

The check was necessary, he said, “Because we didn’t want to be fooled. The canoe could have been a Boy Scout project from the 1950s.”

The results showed not a replica built by pre-teen boys but the real deal, a canoe from AD 800. From that point on, Skibo said, WHS Director Christian Overland was all-in with support for recovering, preserving and sharing this amazing object. That is also certainly in keeping with Skibo’s own ethic, as he explained, in his role serving as the people’s archeologist.

On Nov. 2, 2021, after weeks of planning, preparation and involvement by WHS staff and the Dane County Sheriff’s Office Dive Team, the canoe was recovered from the lake. A WHS video details the process. Recovery was deemed necessary because as sediment had shifted and the canoe was partially uncovered, disintegration would quickly follow.

Bringing the canoe into shore from Lake Mendota in Madison, Wisconsin, represented the culmination of weeks of planning and team contributions. Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society

Skibo said at every step of the process since discovery, Wisconsin’s Indigenous leaders have been consulted, and they also supported the removal, and now, preservation work. Further, Skibo said, repatriating human remains and sacred objects is a well-established practice of the WHS. In this instance, the canoe was in the public domain, is state property and had neither human remains nor sacred objects as part of the site.

On a recent visit to a WHS preservation facility, this writer was fortunate to see the canoe. The old adage, “if this object could talk, what would it say,” came to mind. It was a powerful moment to reflect that it had been more than a millennium since people had used this vessel, which resembles a slightly charred version of a modern-day paddleboard, but one with narrow and shallow sides. It is 15 feet long, weighs 280 pounds and has a gaping and practically symmetrical hole in the base of one end, likely the damage that sealed its sinking fate. At the other end of the canoe, the one that had been exposed from the lakebed and originally caught Thomsen’s eye, it is slightly split.

Its beginnings? It was hewn from a felled white oak tree. Fire was perhaps used to assist in hollowing it out. It probably sank near to where it was made, offshore from a small seasonal village of a woodland people who hunted, fished and tended gardens of corn, sunflowers and squash. These people were also mound builders.

Its future? The canoe is now resting in a wood-framed crib-like structure layered with three pond liners and filled with 15 inches of purified water as part of a nearly three-year-long preservation process that includes replacing the water that is essentially the only thing maintaining the canoe’s structure via osmosis with polyethylene glycol, which will coat and strengthen the canoe’s interior cells. At the end of the process, the canoe will be freeze-dried at minus 22 degrees Celsius to remove any remaining water.

It is expected that this ancient shipwreck will be given a place of pride in a new WHS museum anticipated to open in 2026 in Madison. Upon display, this writer looks forward to experiencing the powerful feelings the canoe first elicited. It is also a celebration of the ingenuity and dedication of WHS staff who have done and will continue to tell the story of this canoe and the people who created it.