Friends of Lincoln Park board members and neighbors gather at a Milwaukee County Board budget hearing to protest the planned closure of an aquatic center in their neighborhood. Cheryl Bledsoe is on the second from left. Image credit: Friends of Lincoln Park

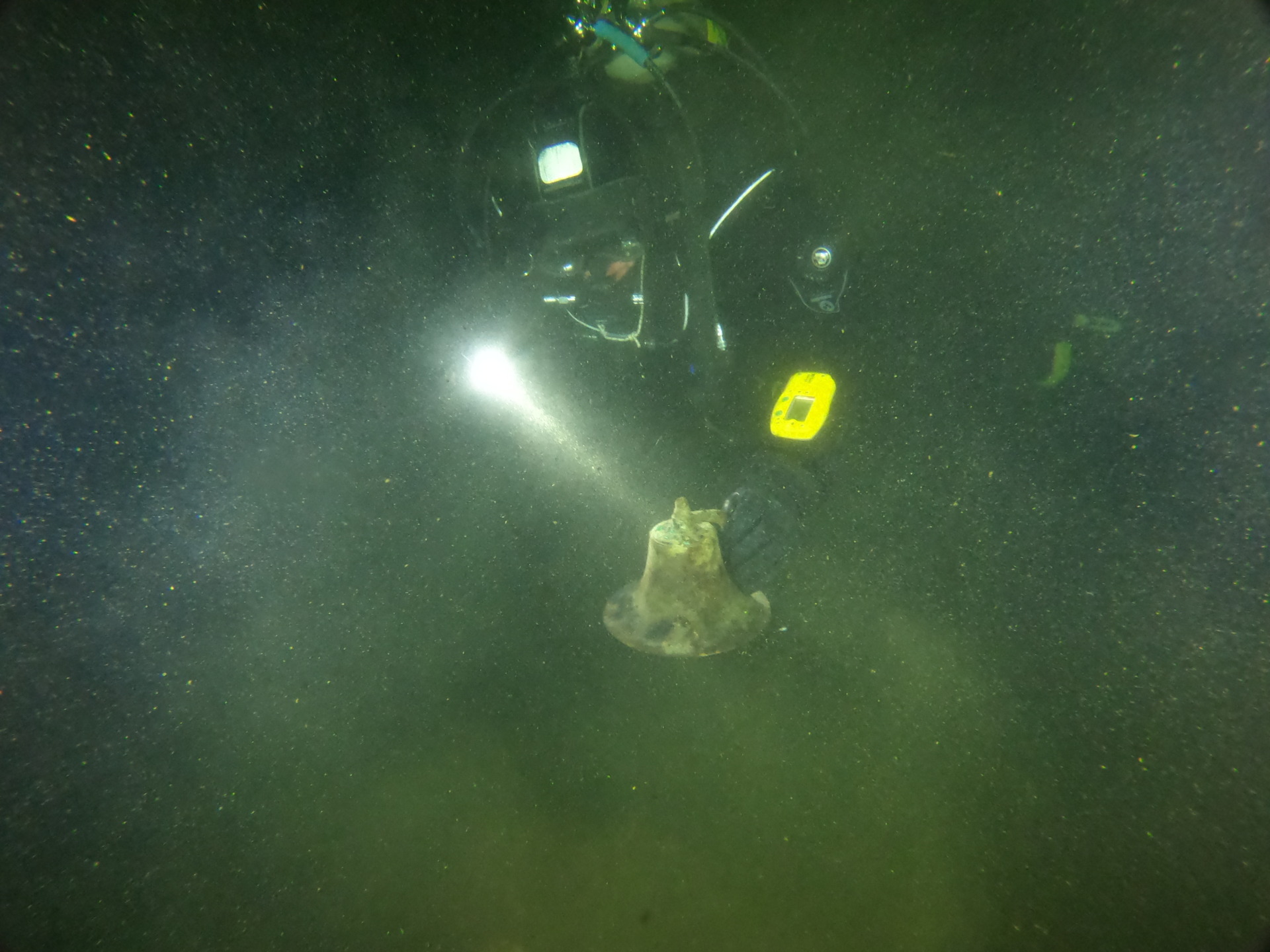

In 2018, a group of children and their parents gathered in a hallway in the Milwaukee County Courthouse, holding signs and chanting. The signs said, “Closing our pool is mean” and “Don’t drown us in bureaucracy!”

They were protesting the proposed closure of the Schulz Aquatic Center, a relatively new facility in their Lincoln Park neighborhood that had been targeted due to county budget shortages. Many of the protesters were African American, which reflected the makeup of their neighborhood on Milwaukee’s north side.

Cheryl Bledsoe, an assistant principal at the time at Cross Trainers Academy and a board member of the Friends of Lincoln Park, announced to the news video cameras at the protest, “. . . The pool should remain open so our current African American youths have the opportunity to receive swimming lessons at that pool . . . I don’t think it’s fair that since 1995, five public pools on the north side have been closed . . . Lincoln Park pool will not close under my watch.”

The Schulz Aquatic Center in Milwaukee was built in 2009. Image credit: Quorum Architects Inc.

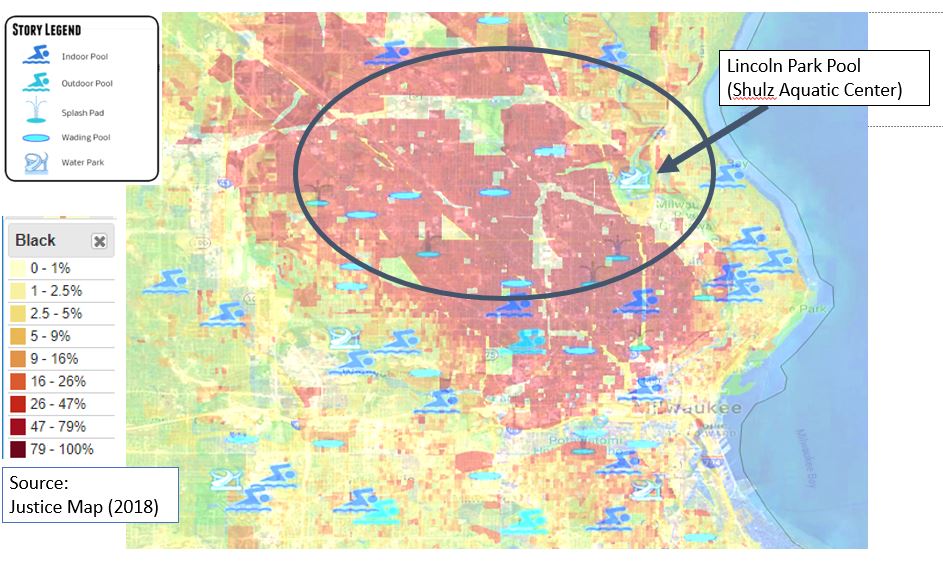

The data behind Bledsoe’s statement about the number of pool closures came from a mapping project undertaken by Deidre Peroff, Wisconsin Sea Grant’s social science outreach specialist in Milwaukee. The interactive Google Earth map she developed with Reflo, a local nonprofit, provided pivotal information, which, when brought to light by the friends group, ultimately helped convince the Milwaukee County Board to keep the pool open and make their budget cuts elsewhere.

“Basically, we looked at where swimming pools are and where they have been historically, all the way back to the 1930s,” Peroff said. “What the map indicated pretty clearly is they’re mostly closing in the north side of the city, which is a predominantly Black community.”

Peroff said she started the mapping project as part of her duties as co-chair of an education and recreation committee of Milwaukee Water Commons, a group that’s working to make Milwaukee a model water city.

“The two main goals of that initiative were that every child and adult in Milwaukee would have meaningful water experiences and to launch a comprehensive effort to change culture around swimming and improve access to swimming facilities,” Peroff said.

The committee gathered various Milwaukee organizations together to discuss how to accomplish these goals and received an earful about past efforts that had failed due to socio-cultural, financial, historical, political and even transportation barriers.

This map shows the “swimming pool desert” in north Milwaukee. If the Schulz Aquatic Center pool had been closed, only splash pads would have been available in this predominantly Black neighborhood. Children can’t learn how to swim on splash pads. Image credit: Deidre Peroff

Peroff said that myths about Black people and swimming, combined with a long history of segregation around swimming are hard to overcome.

Pool access for Black communities is a vital issue because, according to the USA Swimming Foundation (2017), 64% of African American children have no or low swimming ability. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, this may be why Black children, without regard to age or income, are up to 5.5 times more likely to drown than white children.

David Thomas, board secretary for the Friends of Lincoln Park, said the timing was fortunate for their information needs in fighting the pool closure. “When all this hit the fan and they announced the pool closing, Deidre had already started this research. It was a very fortunate chain of events that the research was already going on.”

Thomas sent out an email to the Friends group with a call to action to save the pool, which included a link to the pool closure map.

Bledsoe, who is African American, said she learned how to swim at a previous pool in Lincoln Park. She said the Schulz Aquatic Center closure issue was an opportunity for her students to learn how to peacefully advocate for their community. It showed them that public officials “aren’t untouchable. You can talk to them, you can call them. Their information is available.”

She said their successful protest was about more than just saving the pool. It helped build the youths’ confidence and self-esteem. “There were lives changed as a result of that, and people fighting for something very meaningful.”

Bledsoe’s own parents were so proud of their daughter’s role in keeping the aquatic center open, they framed a copy of the “Milwaukee Journal Sentinel” newspaper story, displaying it in their living room.

David Thomas, Friends of Lincoln Park board member. Image credit: Friends of Lincoln Park

Peroff credits the Friends group’s strong community relationships for their success. They were able to call on people who were already invested in the park and cared about the aquatic center. “That was one reason they were able to move so quickly, and then also use the map and some other data to tell the story they needed.”

A spin-off project, undertaken in 2019, had Peroff looking at the impact of swimming programs on underserved communities in Milwaukee. She hired Emily Tolliver, a professional master’s student, to interview seven swimming organizations about how they address the issue of diversity and access to swimming resources in their programming.

She is still analyzing the data but said one thing is coming out clearly. “We found that the programs that were more successful in being diverse said the best thing was having African American or Black role models – teachers or lifeguards or staff – who are part of the swimming program.” She said these programs worked extra hard to recruit people of color to be part of their organizations.

Peroff said addressing these wickedly difficult issues is satisfying, but they are complex. “It’s not like one approach is going to fix any problem. We have to understand the barriers at a much deeper level.”